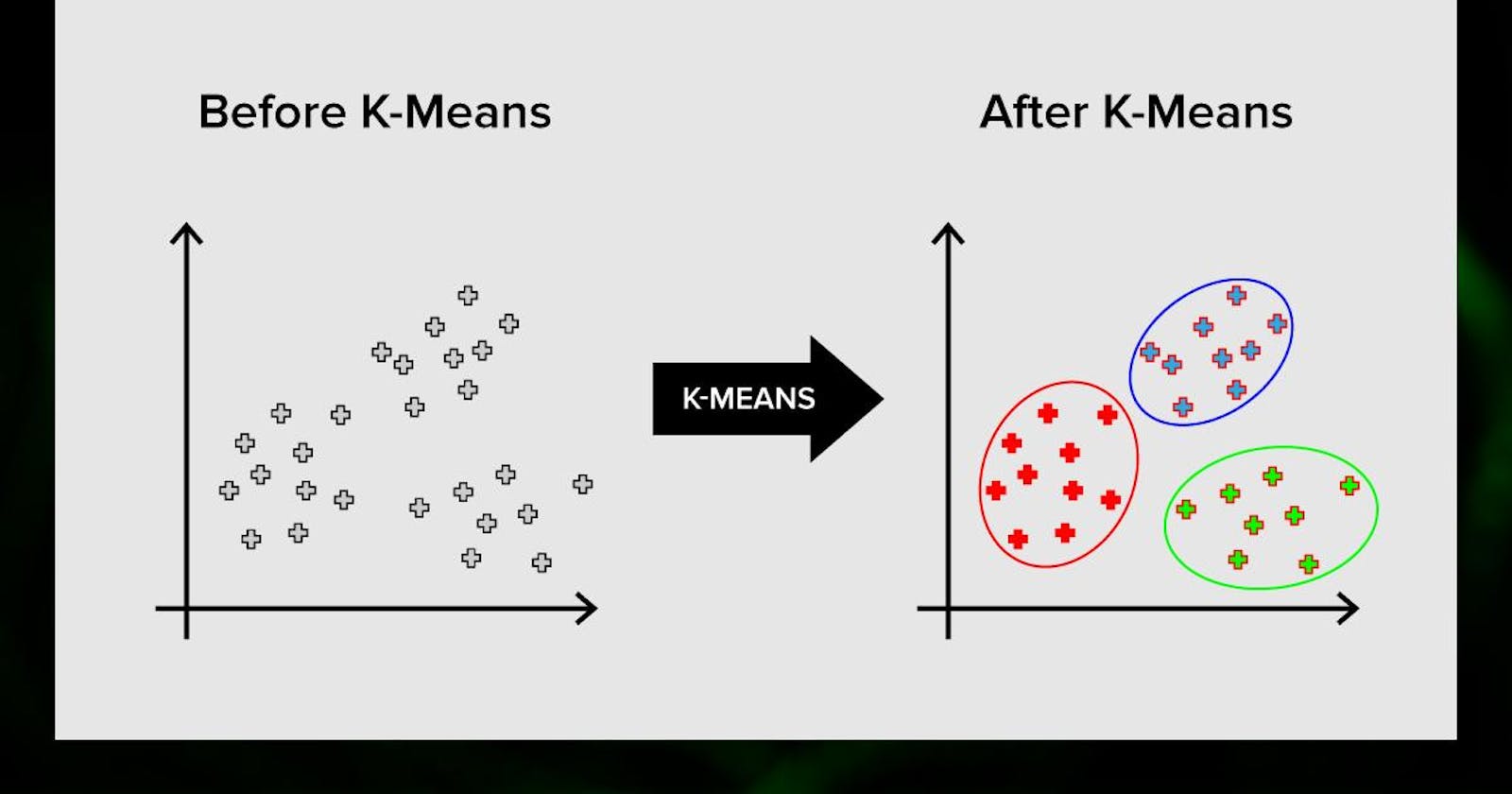

The k-means clustering method is an unsupervised machine learning technique that helps group similar data objects together in a dataset. While many types of clustering methods are available, k-means is one of the oldest and easiest to understand. This makes it relatively simple to implement k-means clustering in Python, even for beginners in programming and data science.

If you're interested in learning how and when to use k-means clustering in Python, you've come to the right place. In this tutorial, you'll walk through a complete k-means clustering process using Python, starting from data preprocessing to evaluating the results.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn:

What k-means clustering is

When to use k-means clustering to analyze your data

How to implement k-means clustering in Python with scikit-learn

How to select a meaningful number of clusters

Writing Your First K-Means Clustering Code in Python

Thankfully, there’s a robust implementation of k-means clustering in Python from the popular machine-learning package scikit-learn.

The code in this tutorial requires some popular external Python packages and assumes that you’ve installed Python with Anaconda. For more information on setting up your Python environment for machine learning in Windows, read through Setting Up Python for Machine Learning on Windows.

import tarfile

import urllib

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.metrics import silhouette_score, adjusted_rand_score

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder, MinMaxScaler

uci_tcga_url = (

"https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/00401/"

)

archive_name = "TCGA-PANCAN-HiSeq-801x20531.tar.gz"

# build the url

full_download_url = urllib.parse.urljoin(uci_tcga_url, archive_name)

# download the file

r = urllib.request.urlretrieve(full_download_url, archive_name)

# extract the data from the archive

tar = tarfile.open(archive_name, "r:gz")

tar.extractall()

tar.close()

datafile = "TCGA-PANCAN-HiSeq-801x20531/data.csv"

labels_file = "TCGA-PANCAN-HiSeq-801x20531/labels.csv"

data = np.genfromtxt(

datafile, delimiter=",", usecols=range(1, 20532), skip_header=1

)

true_label_names = np.genfromtxt(

labels_file, delimiter=",", usecols=(1,), skip_header=1, dtype=str

)

In this code snippet, we initiate the process of preparing a dataset for the k-means clustering algorithm, focusing on the TCGA-PANCAN-HiSeq dataset often used in cancer genomics research. The provided Python code utilizes the urllib library to construct a download URL by joining the base UCI Machine Learning Repository URL with the specific dataset's compressed archive name. Subsequently, the urllib.request.urlretrieve function is employed to download the dataset, and the tarfile module is utilized to open the compressed archive in read mode ("r:gz"). The contents of the archive are then extracted using the extractall method, and the archive file is properly closed. This process is crucial as it ensures the availability of the TCGA-PANCAN-HiSeq dataset, enabling subsequent analysis and application of the k-means clustering algorithm to unveil patterns and insights in cancer genomics data.

data[:5, :3]

array([[0. , 2.01720929, 3.26552691],

[0. , 0.59273209, 1.58842082],

[0. , 3.51175898, 4.32719872],

[0. , 3.66361787, 4.50764878],

[0. , 2.65574107, 2.82154696]])

true_label_names[:5]

array(['PRAD', 'LUAD', 'PRAD', 'PRAD', 'BRCA'], dtype='<U4')

Data sets usually contain numerical features that have been measured in different units, such as height (in inches) and weight (in pounds). A machine learning algorithm would consider weight more important than height only because the values for weight are larger and have higher variability from person to person.

Machine learning algorithms need to consider all features on an even playing field. That means the values for all features must be transformed to the same scale.

The process of transforming numerical features to use the same scale is known as feature scaling. It’s an important data preprocessing step for most distance-based machine learning algorithms because it can have a significant impact on the performance of your algorithm.

There are several approaches to implementing feature scaling. A great way to determine which technique is appropriate for your dataset is to read scikit-learn’s preprocessing documentation.

In this example, you’ll use the StandardScaler class. This class implements a type of feature scaling called standardization. Standardization scales, or shifts, the values for each numerical feature in your dataset so that the features have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1:

label_encoder = LabelEncoder()

true_labels = label_encoder.fit_transform(true_label_names)

true_labels[:5]

array([4, 3, 4, 4, 0])

label_encoder.classes_

array(['BRCA', 'COAD', 'KIRC', 'LUAD', 'PRAD'], dtype='<U4')

Now the data are ready to be clustered. The KMeans estimator class in scikit-learn is where you set the algorithm parameters before fitting the estimator to the data. The scikit-learn implementation is flexible, providing several parameters that can be tuned.

Here are the parameters used in this example:

initcontrols the initialization technique. The standard version of the k-means algorithm is implemented by settinginitto"random". Setting this to"k-means++"employs an advanced trick to speed up convergence, which you’ll use later.n_clusterssets k for the clustering step. This is the most important parameter for k-means.n_initsets the number of initializations to perform. This is important because two runs can converge on different cluster assignments. The default behavior for the scikit-learn algorithm is to perform ten k-means runs and return the results of the one with the lowest SSE.max_itersets the number of maximum iterations for each initialization of the k-means algorithm.

n_clusters = len(label_encoder.classes_)

preprocessor = Pipeline(

[

("scaler", MinMaxScaler()),

("pca", PCA(n_components=2, random_state=42)),

]

)

pipe = Pipeline([("preprocessor", preprocessor), ("clusterer", clusterer)])

Statistics from the initialization run with the lowest SSE are available as attributes of kmeans after calling .fit():

pipe.fit(data)

Pipeline(steps=[('preprocessor',

Pipeline(steps=[('scaler', MinMaxScaler()),

('pca',

PCA(n_components=2, random_state=42))])),

('clusterer',

Pipeline(steps=[('kmeans',

KMeans(max_iter=500, n_clusters=5, n_init=50,

random_state=42))]))])

The silhouette coefficient is a measure of cluster cohesion and separation. It quantifies how well a data point fits into its assigned cluster based on two factors:

How close the data point is to other points in the cluster

How far away the data point is from points in other clusters

Silhouette coefficient values range between -1 and 1. Larger numbers indicate that samples are closer to their clusters than they are to other clusters.

In the scikit-learn implementation of the silhouette coefficient, the average silhouette coefficient of all the samples is summarized into one score. The silhouette score() function needs a minimum of two clusters, or it will raise an exception.

preprocessed_data = pipe["preprocessor"].transform(data)

predicted_labels = pipe["clusterer"]["kmeans"].labels_

silhouette_score(preprocessed_data, predicted_labels)

0.511877552845029

adjusted_rand_score(true_labels, predicted_labels)

0.722276752060253

As mentioned earlier, the scale for each of these clustering performance metrics ranges from -1 to 1. A silhouette coefficient of 0 indicates that clusters are significantly overlapping one another, and a silhouette coefficient of 1 indicates clusters are well-separated. An ARI score of 0 indicates that cluster labels are randomly assigned, and an ARI score of 1 means that the true labels and predicted labels form identical clusters.

Since you specified n_components=2 in the PCA step of the k-means clustering pipeline, you can also visualize the data in the context of the true labels and predicted labels. Plot the results using a pandas DataFrame and the seaborn plotting library:

pcadf = pd.DataFrame(

pipe["preprocessor"].transform(data),

columns=["component_1", "component_2"],

)

pcadf["predicted_cluster"] = pipe["clusterer"]["kmeans"].labels_

pcadf["true_label"] = label_encoder.inverse_transform(true_labels)

plt.style.use("fivethirtyeight")

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

scat = sns.scatterplot(

"component_1",

"component_2",

s=50,

data=pcadf,

hue="predicted_cluster",

style="true_label",

palette="Set2",

)

scat.set_title("Clustering results from TCGA Pan-Cancer\nGene Expression Data")

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1), loc=2, borderaxespad=0.0)

plt.show()

Tuning a K-Means Clustering Pipeline

Your first k-means clustering pipeline performed well, but there’s still room to improve. That’s why you went through the trouble of building the pipeline: you can tune the parameters to get the most desirable clustering results.

The process of parameter tuning consists of sequentially altering one of the input values of the algorithm’s parameters and recording the results. At the end of the parameter tuning process, you’ll have a set of performance scores, one for each new value of a given parameter. Parameter tuning is a powerful method to maximize performance from your clustering pipeline.

By setting the PCA parameter n_components=2, you squished all the features into two components, or dimensions. This value was convenient for visualization on a two-dimensional plot. But using only two components means that the PCA step won’t capture all of the explained variance of the input data.

Explained variance measures the discrepancy between the PCA-transformed data and the actual input data. The relationship between n_components and explained variance can be visualized in a plot to show you how many components you need in your PCA to capture a certain percentage of the variance in the input data. You can also use clustering performance metrics to evaluate how many components are necessary to achieve satisfactory clustering results.

In this example, you’ll use clustering performance metrics to identify the appropriate number of components in the PCA step. The Pipeline class is powerful in this situation. It allows you to perform basic parameter tuning using a for loop.

Iterate over a range of n_components and record evaluation metrics for each iteration:

# Empty lists to hold evaluation metrics

silhouette_scores = []

ari_scores = []

for n in range(2, 11):

# This set the number of components for pca,

# but leaves other steps unchanged

pipe["preprocessor"]["pca"].n_components = n

pipe.fit(data)

silhouette_coef = silhouette_score(

pipe["preprocessor"].transform(data),

pipe["clusterer"]["kmeans"].labels_,

)

ari = adjusted_rand_score(

true_labels,

pipe["clusterer"]["kmeans"].labels_,

)

# Add metrics to their lists

silhouette_scores.append(silhouette_coef)

ari_scores.append(ari)

Plot the evaluation metrics as a function of n_components to visualize the relationship between adding components and the performance of the k-means clustering results:

plt.style.use("fivethirtyeight")

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.plot(

range(2, 11),

silhouette_scores,

c="#008fd5",

label="Silhouette Coefficient",

)

plt.plot(range(2, 11), ari_scores, c="#fc4f30", label="ARI")

plt.xlabel("n_components")

plt.legend()

plt.title("Clustering Performance\nas a Function of n_components")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

There are two takeaways from this figure:

The silhouette coefficient decreases linearly. The silhouette coefficient depends on the distance between points, so as the number of dimensions increases, the sparsity increases.

The ARI improves significantly as you add components. It appears to start tapering off after

n_components=7, so that would be the value to use for presenting the best clustering results from this pipeline.

Like most machine learning decisions, you must balance optimizing clustering evaluation metrics with the goal of the clustering task. In situations when cluster labels are available, as is the case with the cancer dataset used in this tutorial, ARI is a reasonable choice. ARI quantifies how accurately your pipeline was able to reassign the cluster labels.

The silhouette coefficient, on the other hand, is a good choice for exploratory clustering because it helps to identify subclusters. These subclusters warrant additional investigation, which can lead to new and important insights.

Conclusion

You now know how to perform k-means clustering in Python. Your final k-means clustering pipeline was able to cluster patients with different cancer types using real-world gene expression data. You can use the techniques you learned here to cluster your own data, understand how to get the best clustering results and share insights with others.

In this tutorial, you learned:

What the popular clustering techniques are and when to use them

What the k-means algorithm is

How to implement k-means clustering in Python

How to evaluate the performance of clustering algorithms

How to build and tune a robust k-means clustering pipeline in Python

How to analyze and present clustering results from the k-means algorithm

🎙️ Message for Next Episode:

We are now ready to move on to our second unsupervised learning algorithm, which is anomaly detection. This algorithm helps in identifying unusual or anomalous patterns in a given dataset. Anomaly detection is one of the most commercially important applications of unsupervised learning.

Resources For Further Research

Coursera - Machine Learning Specialization

This Article is heavily inspired by this Course so I will also recommend you to check this course out, there is an option to watch the

course for freeor you can buy the course to gain aSpecialization Certificate.Optional labs provided in this article are from this course itself.

"Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow" by Aurélien Géron:

- A practical guide covering various machine learning concepts and implementations.

By the way…

Call to action

Hi, Everydaycodings— I’m building a newsletter that covers deep topics in the space of engineering. If that sounds interesting, subscribe and don’t miss anything. If you have some thoughts you’d like to share or a topic suggestion, reach out to me via LinkedIn or X(Twitter).

References

And if you’re interested in diving deeper into these concepts, here are some great starting points:

Kaggle Stories - Each episode of Kaggle Stories takes you on a journey behind the scenes of a Kaggle notebook project, breaking down tech stuff into simple stories.

Machine Learning - This series covers ML fundamentals & techniques to apply ML to solve real-world problems using Python & real datasets while highlighting best practices & limits.